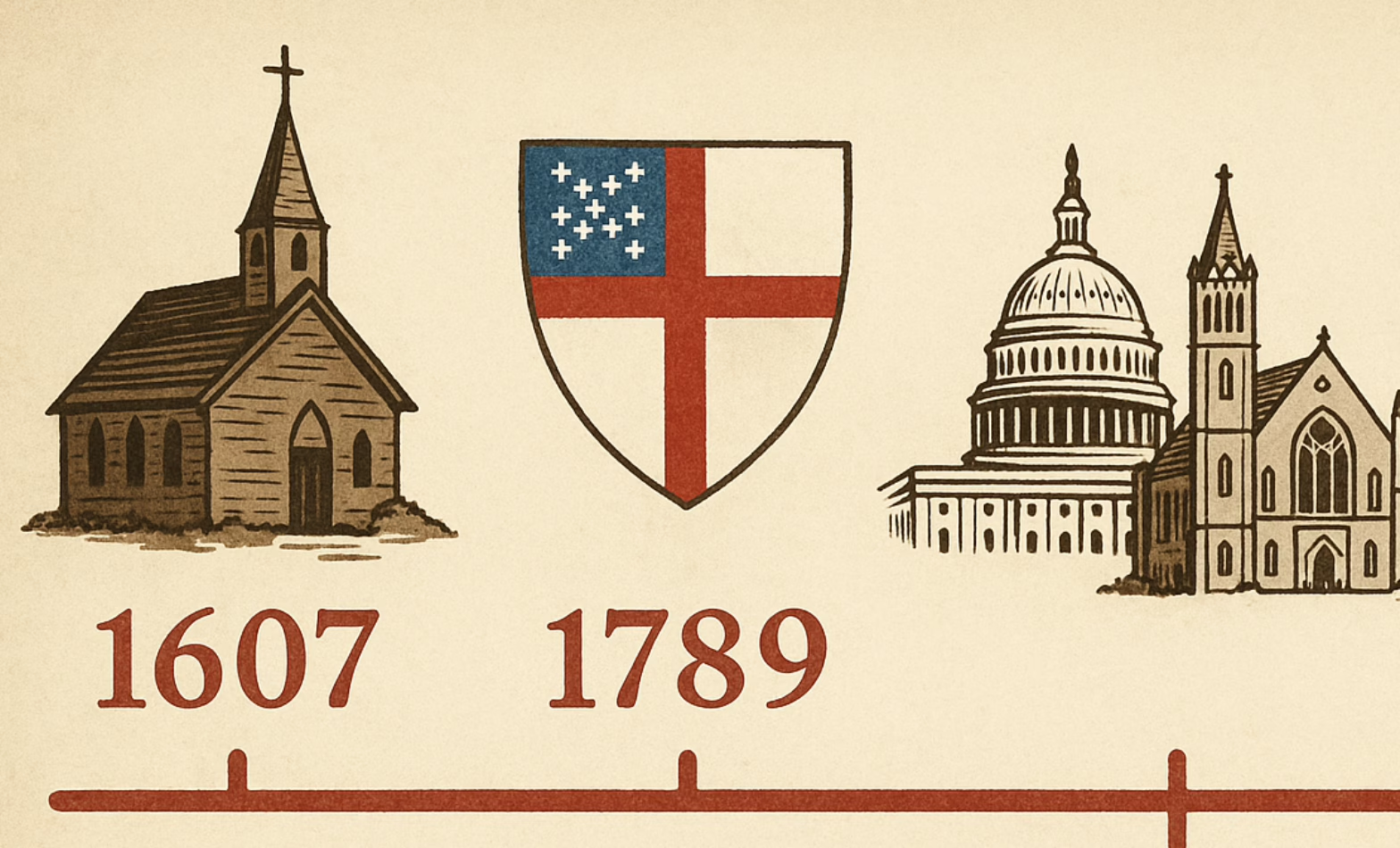

Understanding the history of the American Anglican and Episcopal Church tradition and its roots in the Anglican Church of England is essential to understanding the denominational history of Protestant Christianity in the United States. My short overview here traces the journey from early Christianity to the establishment of the Episcopalian and Anglican Churches in America (Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States)

I’ve given a longer version of this history in video format. In that video I answer some fun questions like:

- Did you know the first Communion service in the New World happened on the West Coast using the Anglican Book of Common Prayer?

- What church did American members of the Church of England (like George Washington) belong to after the English lost the Revolutionary War?

- How did Anglicanism become the Episcopal Church in the United States?

Early Christian Foundations and the Church of England

Christianity, once persecuted under Roman emperors such as Nero (54–68 AD), Domitian (81–96 AD), Trajan (98–117 AD), Decius (249–251 AD), and Diocletian (284–305 AD), began to flourish under Emperor Constantine (306–337 AD). In A.D. 325, the First Council of Nicaea was convened as the Church transitioned from persecuted to a place of honor and influence in the Empire. This allowed the Church to formally define what it meant to be a Christian and fortify the polity (church government) handed down by the Apostles.

This newly favored status allowed Christianity not only to clarify its doctrines and structure but also to spread more freely throughout the empire and beyond—including to the British Isles, where the seeds of the faith had already taken root long before the East-West divide of 1054. (Note: 1054 is a useful date, but not entirely comprehensive.)

In 1054, the Great Schism divided Christianity into Eastern (Greek) and Western (Latin) branches (to simplify things greatly). Long before this, Christianity had reached Britain, possibly through early converts and Roman soldiers. Saint Alban, Britain’s first martyr, died in the third century, and early bishoprics were established in London, York, and Lincoln. Additionally, Legends and pious traditions surround figures like Joseph of Arimathea, who is said to have brought the Holy Grail to Glastonbury, and Bishop Aristobulus, believed by some to be one of the first Christian missionaries to Britain and even ordained by the original apostles themselves.

From Roman Britain to English Reformation

After the withdrawal of Roman legions in A.D. 401, invading pagan tribes attacked and drove some British Christians into Wales and Ireland. Though nearly extinguished, early Celtic Christianity preserved remnants of its apostolic heritage—including distinct liturgical practices of St. John and his calendar—which eventually led to noticeable divergences from the continental (Roman and Gallicean) Christian traditions. The Christian reconversion of England began in earnest through Irish missionaries like St. Columba to Iona and Roman missions led by Saint Augustine of Canterbury in 597 at the request of Pope St. Gregory the Great. These Roman missionaries were successful in Southern England at Kent (Kent-erbury=Canterbuy) and went on to discover the remnants of Celtic Bishoprics as they travelled Northward. These two traditions combined their Apostolic lines at the Synod of Whitby in 664 AD. This council united the Celtic Church with Rome while also recognizing the pre-existing apostolic lineage of the English branch of the Catholic Church.

Over the centuries, the Church in England came increasingly under papal (Roman) control. The Roman Church was transformed as Muslim conquest allowed the Pope’s political and ecclessiatical power to grow over the centuries. Four of the five ancient Nicene Pentarchial Sees fell under Muslim persecution—Alexandria in 641, Antioch in 637, Jerusalem in 638, and finally Constantinople was sacked by Rome’s Latin Crusaders in 1204—leaving Rome as the dominant patriarchal see.

In England, the 1066 Norman conquest led by William the Conqueror restructured the church by removing the local Anglo-Saxon bishops for Norman (think “French”) candidates for those who would be loyal to William. Ironically, here the English church would also invoke the ancient privilege of “Royal Supremacy” over the church to prevent the Pope or papal legates from imposing Bishops over the English Church. This would become an issue during the reign of Henry II related to the death of Thomas Becket—Henry would reinforce the idea that the English monarch had jurisdiction over the church in his realm. English Kings appealed to the precedent of Alfred the Great (9th century) who believed the Christian King was to have the final say over episcopal appointments.

By the 14th century, growing dissatisfaction with papal abuses, moral corruption, and financial exactions—especially after the Black Death—led to statutes like Provisors and Praemunire, restricting Roman (papal) influence in England and conflict with the British Crown. In England the Reformation did not begin with Luther, but was the inevitable reaction of English churchman against centuries of the Pope’s overreach.

The English Reformation and the Rise of Anglicanism

The English Reformation was then inflamed by the broader theological upheavals of the Continental Reformation, particularly the influence of Martin Luther’s evangelical movement. This ferment, combined with Henry VIII’s protracted dispute with the papacy over the annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, brought tensions between the English Crown and Rome to a final breaking point. The crisis culminated in 1534, when the English Parliament, through the Act of Supremacy, formally declared that the Bishop of Rome held no jurisdiction over the Church in England.

“Be it enacted… that the King’s Majesty shall be taken, accepted, and reputed the only Supreme Head on earth of the Church of England…”

“…the Bishop of Rome, otherwise called the Pope, hath no greater jurisdiction conferred upon him by God in Holy Scripture in this realm of England than any other foreign bishop.”

Thomas Cranmer, as Archbishop of Canterbury, helped shape the emerging Anglican Church.

Following Henry’s death, the Church of England began to take on a more reformed character during the reign of his son, Edward VI. During this time, the Book of Common Prayer was completed in English and worship was restored to a historic order that reflected its earlier apostolic heritage while maintaining catholic episcopacy and sacramental life. Edward was followed by Mary (“Bloody Mary”) who brought the English Church back under Rome until she was succeeded by Queen Elizabeth in 1558.

The Church of England in the American Colonies

It was during the Reign of Elizabeth that the English Church would spread abroad. Sir Francis Drake’s voyage to California would include celebrating Holy Communion in 1579 according to the Book of Common Prayer in San Francisco. (See my article: American Anglicanism Began in California) This was the first English language and first Prayer Book service in North America. In 1607, Rev. Robert Hunt would celebrate the English service at Jamestown. By the time of the Revolutionary War, There were Anglican Churches in all of the American colonies. Several notable parishes were founded, including King’s Chapel in Boston (1687), Christ Church in Philadelphia (1695), and Trinity Church in New York (1697).

The American Revolution and Anglican Realignment

During the American Revolution, the Church of England in America suffered due to its association with the British crown. Clergy were required to have taken oaths of loyalty to the king, yet the King never sent a Bishop to oversee the colonies. The colonies were under the care of the Bishop of London who never once visited the colonies. During the American Revolutionary War, clergy such as Dr. William White served as chaplains to both the Continental Army and the Continental Congress. Notably, a significant number of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and later the U.S. Constitution were members of the Church of England and active participants in the Anglican tradition, including President George Washington.

After American independence, Anglicans in the newly formed United States could no longer remain under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of London or the authority of the English Parliament. In response to the need for episcopal leadership, the clergy of Connecticut elected the Rev. Samuel Seabury as bishop in 1783. However, due to the requirement of swearing political allegiance to the Crown, English bishops refused to consecrate him. As a result, Seabury turned to the Scottish non-juring bishops—clergy who had remained loyal to the House of Stuart and operated independently of the laws governing the Established Church of England. He was consecrated in Aberdeen on November 14, 1784, becoming the first bishop of the American Anglicans now organized as the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States.

This forced a change in English law that permitted further episcopal consecrations without requiring an oath of allegiance to the king. In 1787, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, along with the Bishops of Bath and Wells and Peterborough, consecrated Dr. Samuel Provoost (New York) and Dr. William White (Pennsylvania) at Lambeth Palace, thereby also providing succession from the English to the American Church. Though the relationship would remained strained between the two until after the coalescing of Anglican Communion at the first Lambeth Conference in 1867.

Founding of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the USA

In 1789, a General Convention (national synod) was held in Philadelphia. The Protestant Episcopal Church adopted its own Constitution and revised Book of Common Prayer, maintaining Anglican liturgical traditions (although adding some Scottish customs) while maintaining ecclesiastical independence or jurisdictional autocephaly from the Scottish and English churches. Despite initial sluggish growth—partly due to clergy hesitating to move westward—the Episcopal Church began its national expansion.

Expansion, Education, and Civil War

The 19th century saw the rise of Episcopal seminaries:

- General Theological Seminary (1819, New York)

- Virginia Theological Seminary (1823, Alexandria)

These institutions emphasized training clergy and missionaries. Monastic communities, schools, colleges, and hospitals flourished. Leaders like Bishop Philander Chase (Bishop of Ohio, 1819) and Bishop Jackson Kemper (first Missionary Bishop to American Midwest and founder of Nashotah House) were instrumental in evangelizing the American frontier. Following in the missionary footsteps of Kemper and Chase, Bishop William Ingraham Kip was sent to California in 1853 as the first Episcopal missionary bishop to the Pacific coast. The American Episcopal Church was now intercontinental.

During the Civil War, southern dioceses withdrew from the Protestant Episcopal Church and formed the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America (PEC-CSA). While the most ardent supporters of the Southern cause—such as Bishop Stephen Elliott of Georgia, who served as Presiding Bishop of the Confederate Episcopal Church, and Bishop Leonidas Polk of Louisiana, who also held the rank of Confederate general—did not live to attend the postwar General Convention, their dioceses quickly rejoined the postwar Episcopal Church without censure or penalty.

The Modern Episcopal Church and Ecumenical Vision

However, in the decades that followed, internal tensions emerged—not over sectional politics, but over theological direction, liturgical practice, and ecclesial relationships. As I explain in my article, Are You Anglican or Episcopalian?:

The First Vatican Council fractures the Roman Communion and dissenting “Old Catholic” churches emerge independent from the Pope. This challenged this generation’s assumptions about the direction of the Reformation.

In 1856, William Augustus Muhlenberg (1797-1877) presented a Memorial (a formal petition) to the General Convention of the Episcopal Church. In it, he called for a loosening of what he saw as the Episcopal Church’s exclusiveness regarding denominational authority. Essentially, he suggested that the Episcopal Church should adopt a more apostolic approach to episcopacy, where the bishop could serve as a unifying figure for all evangelical Christians, not just those in the Episcopal or Anglican tradition. By doing so, the episcopacy could become a source of unity among different Protestant groups, promoting greater cooperation and fellowship.

In the late 19th century, the Oxford Movement challenged the earlier Elizabethan consensus that defined Anglicanism as a Reformed Protestant tradition, prompting theological tensions that ultimately led to the formation of the Reformed Episcopal Church in 1873. The Episcopal Church (TEC) continued to shift theologically in the 20th century, adopting liberal stances on major theological and social issues such as women’s ordination (1976), same-sex marriage (2012), and continued revisions to the Book of Common Prayer. In response, many traditional Anglicans left TEC to form what are now called Continuing Anglicans (Congress of St. Louis in 1977 e.g. Anglican Catholic Church, Anglican Province in America) or Anglican Realignment (2008 Common Cause Partnership e.g. Anglican Church in North America) churches.

Leave a Reply