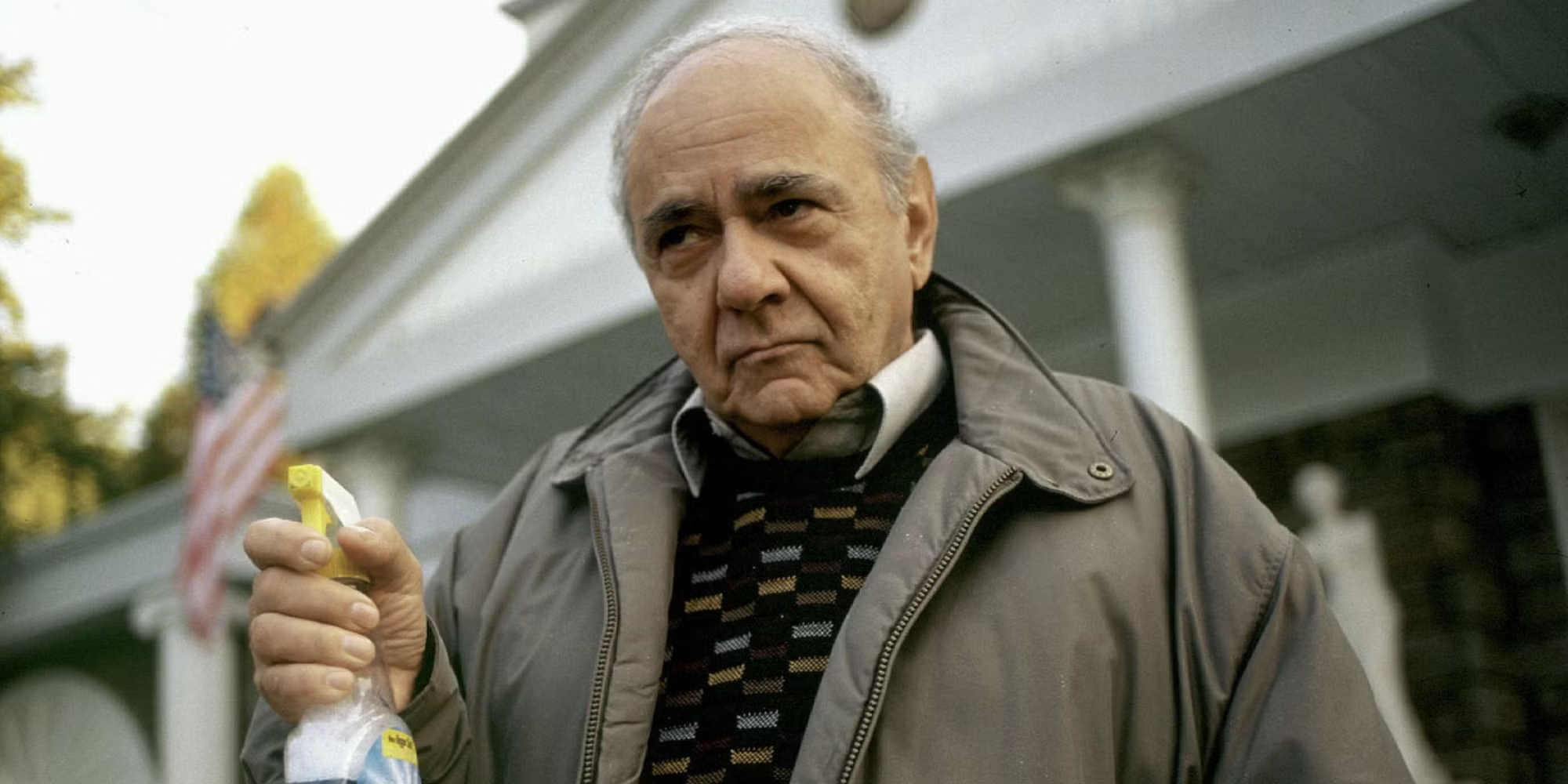

In the movie My Big Fat Greek Wedding, the father of the bride Gus Portokalos shows his misplaced confidence in Greek culture by proudly declaring:

“Give me a word—any word—and I’ll show you how the root of that word is Greek.”

The father, played by the late Michael Constantine, gives ridiculous and often farfetched etymologies for a word’s Greek orgins. One of the most memorable examples is when he claims that the Japanese word kimono comes from the Greek word for winter, χειμώνας (cheimónas). Is there any truth to this? Absolutely not. Kimono is a Japanese word that literally means “thing to wear” (ki = wear, mono = thing) and has no etymological connection to Greek.

That said, Greek has had a significant influence on the English language—especially in academic fields. While only about 5–10% of English vocabulary comes directly from Greek, its impact is especially strong in science, medicine, philosophy, and theology, where Greek roots form the basis for thousands of terms.

Give Me a Denomination—Any Denomination—and I’ll Show You How It’s Anglican

This kind of outsized cultural influence reminds me of Anglicanism’s role in broader American Protestant culture. Everything we love about historic American protestantism is traced back to an English (Anglican) root.

This is why Anglicanism is our Windex. In My Big Fat Greek Wedding, the Greek family also swears by Windex—it’s their cure-all for everything from rashes to stubborn stains. In a similar way, Anglicanism seems to show up everywhere in Protestant tradition, quietly shaping more than most people realize.

The English Bible, public liturgy, hymnody, university model of education, and the major reform movements of the 18th and 19th centuries all point to the Church of England as a primary source of Protestant culture. It may not always bear the Anglican name on the surface, but follow the roots deep enough, and you’ll find they lead back to Canterbury.

The English Bible and the Vernacular Tradition

The Reformation in England produced some of the earliest and most influential vernacular translations of Scripture. William Tyndale, though martyred in 1536, laid the linguistic groundwork for what would eventually become the King James Bible (1611)—a translation that defined English-speaking Protestantism. Over 80% of the KJV’s New Testament text was borrowed directly from Tyndale. Both Tyndale and the KJV translators operated within the ecclesiastical framework of the Church of England. It is hard to overstate the influence of this Bible on American (and Global English-speaking culture).

The Liturgy and Public Worship

The Book of Common Prayer (1549, revised in 1552, 1559, and 1662), compiled by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, not only shaped Anglican worship but became the model for liturgical order across the English-speaking Protestant world. Familiar English phrases such as “Dearly beloved, we are gathered here today”, “ashes to ashes, dust to dust”, and “O God, our help in ages past…”, come directly from this tradition and its English translation choices. The BCP provided a structured, theologically rich form of worship that emphasized Scripture, sacrament, and congregational participation—practices now found in many Protestant denominations.

Education and the Formation of Christian Minds

Institutions like Oxford and Cambridge, long associated with the Church in England, were instrumental in shaping generations of Christian thinkers, clergy, and reformers. Lots of Catholic countries had universities, yet the English tradition of these universities stands out. It was from these institutions that figures like John Wycliffe, and William Tyndale emerged.

The modern Classical Christian education movement owes a significant debt to the Anglican intellectual tradition. Figures such as Thomas Arnold—headmaster of Rugby School and priest in the Church of England—helped define 19th-century ideals of moral and intellectual formation. In the 20th century, Dorothy Sayers, an Anglican scholar, articulated the now-famous “Trivium” model in her essay “The Lost Tools of Learning”, which has become foundational in modern classical school curricula.

Likewise, C.S. Lewis, a devout Anglican and Oxford professor, contributed a compelling defense of classical learning, moral imagination, and Christian formation in works like The Abolition of Man and Mere Christianity. The Anglican legacy is evident in the structure and soul of the Classical Christian school movement today.

Hymnody and Church Songs

Anglicanism has produced some of the most enduring voices in Protestant hymnody. Isaac Watts, often called the father of English hymnody, and William Cowper both emerged from the English tradition. The Wesley brothers, who formed the Methodist movement, were Anglican priests whose hymns remain central to Protestant worship across denominations. Their hymns are marked by doctrinal depth and congregational singing.

Amazing Grace, When I survey the Wondrous Cross, Hark! The Herald Angels Sing, The Church’s One Foundation — are among the Anglican hymns that have crossed into nearly every denomination’s hymnal.

Evangelism and Preaching

The Anglican Church gave rise to one of the most dynamic evangelical figures of the 18th century: George Whitefield. A graduate of Oxford and ordained in the Church of England, Whitefield became a key figure in the First Great Awakening in both Britain and America. His preaching to massive outdoor crowds influenced generations of evangelicals, laying the groundwork for American Christianity’s growth and stability. But the list of respected Anglican preachers is long… but it is worth mentioning Charles Simeon, JC Ryle, Henry Martyn, Samuel Ajayi Crowther, Hudson Taylor, Roland Allen, David Livingstone, Samuel Azariah, Leslie Newbigin and even more modern leaders like John Stott.

Social Reform and Moral Witness

The Anglican tradition also played a key role in the development of modern social conscience commonly called “social justice.” English legacy in leading justice issues goes way back. St. Anselm of Canterbury Anselm openly opposed slavery at the Council of Westminster in 1102, he condemned the slave trade in England, specifically denouncing the practice of selling English people into slavery abroad, marking one of the first formal ecclesiastical condemnations of the slave trade in Western Europe.

And it was William Wilberforce, a devout Anglican and Member of Parliament, led the movement to abolish the British slave trade in 1807. His work was shaped by the evangelical Anglican “Clapham Sect” and supported by figures like John Newton, former slave trader and writer of Amazing Grace.

Anglican moral theology—grounded in natural law, Scripture, and church tradition—helped shape the ethical culture of the English-speaking world, from the Magna Carta in 1215 (influenced by Archbishop Stephen Langton) to abolitionist movements in the 19th century.

Anglican Roots in American Christianity

The Anglican Church was not only the established church of England but also played a foundational role in early American religious life. George Washington was a lifelong Anglican. Many colonial charters were granted under Anglican auspices, and the Episcopal Church—the American continuation of Anglicanism. 11 U.S. Presidents openly identified as Episcopalian—making it the most common religious affiliation among American presidents, historically speaking.

Even the Presbyterian tradition has Anglican roots. John Knox, often regarded as the founder of Scottish Presbyterianism, was ordained as a priest in the Diocese of Diocese of St Andrews and licensed by the English Church (He also served as one of the royal chaplains) and served in English congregations (and even offered English bishoprics) before returning to Scotland. The very idea of a nationally reformed Protestant church, with uniform liturgy and state backing, was inspired by what Knox saw in the Church of England under Edward VI.

A Shared Inheritance

This is not to suggest that all Protestant movements are simply derivatives of Anglicanism. But it is to recognize that the English Church—especially during the Reformation and post-Reformation periods—became a kind of cultural and theological center of gravity for the Protestant world.

So the next time you read the King James Bible, sing a Wesley hymn, or listen to a sermon rooted in Scripture and moral clarity—remember that these gifts often flow from the well of Anglican tradition.

In short: Give Me a Denomination—Any Denomination—and I’ll Show You How It’s Anglican

Leave a Reply